The Year of Our Lord: The End and the Beginning

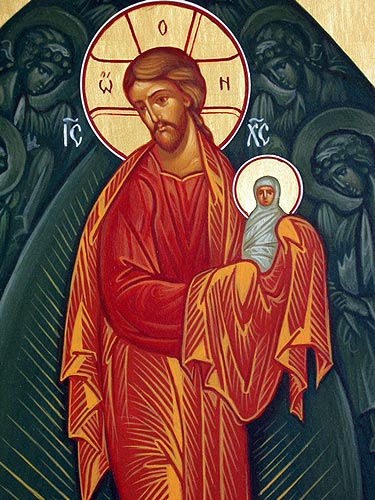

Detail of Dormition icon, showing Christ holding the soul of the Theotokos

Detail of Dormition icon, showing Christ holding the soul of the Theotokos

The Bible and Church life makes sense of time from the vantage point of eternity.

St Peter writes that Christ redeems us from a meaningless existence (I Pet. 1:18). One of the ways this sense of meaning is manifest in the life of the Church is through sanctifying the flow of days.

From the first page of the Bible we see a perception of time different from the modern, mechanical and digital experience: “and there was evening and morning, one day” (Gen. 1:5). The Church begins the week on Saturday night from the vespers that begins the first day – Sunday. In the same way, the year begins in September – the Northern Hemisphere evening of the year. The setting of the Sun signals the end of each day and the beginning of another day. The Dormition of the Theotokos in August prepares the way for her Nativity in September.

In ancient and Orthodox World view the Theotokos (Birthgiver of God) is seen as the Ladder that Jacob, the grandson of Abraham saw (Gen. 28:12), used by One of the Holy Trinity to descend to humanity. Orthodox theology since 431 AD (Council of Ephesus) in contemplating the name ‘Theotokos’ contemplates Christ in Whom divinity and humanity are forever united in one personhood. Furthermore, She is humanity’s first outstretched hand in response to God’s call to salvation. In the Annunciation, She becomes the Bride of God; from the Cross Her beloved Son entrusts Her to John and John to Her, making Her the Mother of all mankind. The ancient Church had a strong existential understanding of Her Motherhood. For centuries, She has been recognised as an image of the Church as Mother: “No one can have God for his father, who has not the Church for his mother.” (St Cyprian of Carthage, ‘Concerning the Unity of the Church’ Ch.VI, 251AD).

The feast of Dormition presents a picture of the Church year falling asleep at its end. The term ‘Dormition’, ‘falling asleep’ describes the painless death of the Ever Virgin. Nevertheless, death is very much part of Her human nature which, according to Orthodox teaching, She is not exempt from. While Her birthgiving of Christ-God from the Holy Spirit was immaculate, Her own birth was from Joachim and Anna, human parents. The Gospels and other New Testament books do not give us any information about the Theotokos after Christ’s Ascension. The most ancient mentions of Dormition are from Dionysius the Areopagite (1st century), St Melito of Sardis, who visited Palestine (died in 190 AD) and St Epiphanius of Cyprus (4th century). The canonical image of the feast shows the apostles surrounding the bier with the body of the Mother of God. Her Son holds her soul depicted as a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes. A multitude of angels prepares to accompany the Lord to heaven with Her soul. Some icons show an enemy of the Church, Temple priest Athonius trying to overturn the bier, while an angel swings a sword to cut off his impious hands. Athonius, healed through the prayers of the Most Holy Mother of God, became a Christian. The festal story tells us that on the third day after the funeral at Gethsemane the apostles opened the tomb for a late comer – Thomas, and found only some of Her vestments and great fragrance filling the tomb. St Melito conveys the pious belief of the early Church that the Lord raised His Holy Mother from the dead before the resurrection of all of humanity in the body.

Each liturgical year begins in anticipation of the feast of the Nativity of the Theotokos on the 8th of September in the Church Calendar. In his preface to the Gospel, St Luke mentions that ‘many’ had already written accounts of the Gospel events. Matthew and Mark are not ‘many’, which means that the Evangelist is referring to certain apocryphal (non-canonical) writings. In sourcing information for the feast of the Nativity of the Theotokos, the Church has used the 2nd century apocryphal ‘Protoevangel of James’. The story of the feast tells us that Joachim and Anna were childless, interpreted as a sign of God’s displeasure in Israel where every family wanted the blessing of having children who would enable the family to be connected to the future Messiah, the Christ. After decades of prayers and sacrifices, when all hope seemed to have disappeared, they are both given a revelation from an angel about the imminent birth of a daughter, bringing glory to them and to their family. They promised that they would dedicate their child to God. When She was born, they gave Her the name ‘Maria’ which means ‘Lady’ and ‘hope’ (‘Maria’ or ‘Mariam’ are a Greek Old Testament rendering of the Hebrew name ‘Miriam’, e.g. the name of the sister of Moses).

A major spiritual and edifying idea behind the story of the feast is that the Holy Virgin is the fruit of long prayers and humility that opens the doors of grace.

The feasts of the Lord beginning with Pascha, Pentecost, Theophany, Christmas and others were the earliest in Church practice, but the feasts of the Theotokos soon followed them. It seems the Nativity of the Theotokos spread from Greece to the Middle East and then Rome and the West from the 400s AD to the 600s AD. It is interesting that the Nestorians celebrate it on 8th September, calling it ‘the Nativity of Lady Miriam’. That is an indirect indication that the feast was known in the Middle East before 431 AD when Nestorians rejected the term ‘Theotokos’ and toned down Her veneration.

Archpriest Nicholas Karipoff